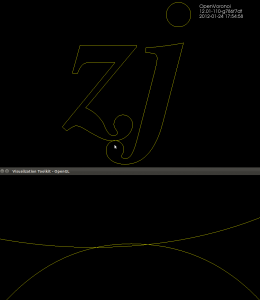

I started working on arc-sites for OpenVoronoi. The first things required are an in_region(p) predicate and an apex_point(p) function. It is best to rapidly try out and visualize things in python/VTK first, before committing to slower coding and design in c++.

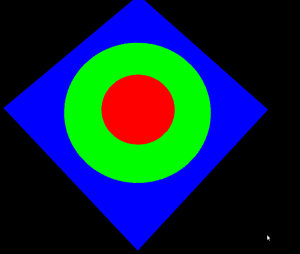

in_region(p) returns true if point p is inside the cone-of-influence of the arc site. Here the arc is defined by its start-point p1, end-point p2, center c, and a direction flag cw for indicating cw or ccw direction. This code will only work for arcs smaller than 180 degrees.

def arc_in_region(p1,p2,c,cw,p):

if cw:

return p.is_right(c,p1) and (not p.is_right(c,p2))

else:

return (not p.is_right(c,p1)) and p.is_right(c,p2) |

def arc_in_region(p1,p2,c,cw,p):

if cw:

return p.is_right(c,p1) and (not p.is_right(c,p2))

else:

return (not p.is_right(c,p1)) and p.is_right(c,p2)

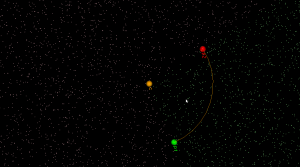

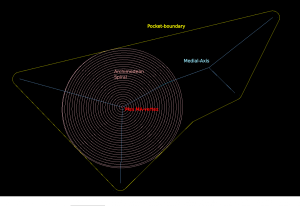

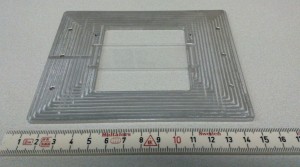

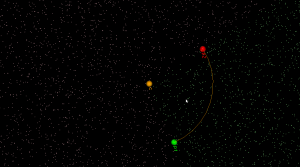

Here randomly chosen points are shown green if they are in-region and pink if they are not.

apex_point(p) returns the closest point to p on the arc. When p is not in the cone-of-influence either the start- or end-point of the arc is returned. This is useful in OpenVoronoi for calculating the minimum distance from p to any point on the arc-site, since this is given by (p-apex_point(p)).norm().

def closer_endpoint(p1,p2,p):

if (p1-p).norm() < (p2-p).norm():

return p1

else:

return p2

def projection_point(p1,p2,c1,cw,p):

if p==c1:

return p1

else:

n = (p-c1)

n.normalize()

return c1 + (p1-c1).norm()*n

def apex_point(p1,p2,c1,cw,p):

if arc_in_region(p1,p2,c1,cw,p):

return projection_point(p1,p2,c1,cw,p)

else:

return closer_endpoint(p1,p2,p) |

def closer_endpoint(p1,p2,p):

if (p1-p).norm() < (p2-p).norm():

return p1

else:

return p2

def projection_point(p1,p2,c1,cw,p):

if p==c1:

return p1

else:

n = (p-c1)

n.normalize()

return c1 + (p1-c1).norm()*n

def apex_point(p1,p2,c1,cw,p):

if arc_in_region(p1,p2,c1,cw,p):

return projection_point(p1,p2,c1,cw,p)

else:

return closer_endpoint(p1,p2,p)

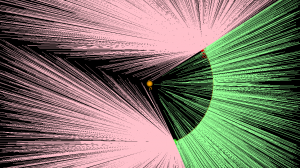

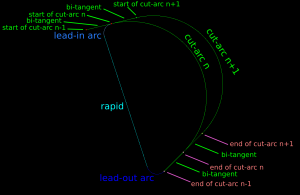

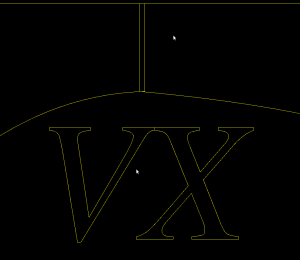

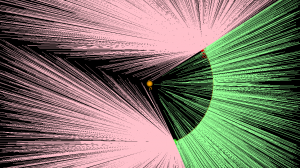

Here a line from a randomly chosen point p to its apex_point(p) has been drawn. Either the start- or end-point of the arc is the closest point to out-of-region points (pink), while a radially projected point on the arc-site is closest to in-region points (green).

The next thing required are working edge-parametrizations for the new type of voronoi-edges that will occur when we have arc-sites (arc/point, arc/line, and arc/arc).